Induction, Made-Man and Destroyer in that order

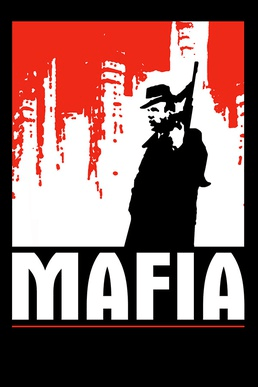

Here, reader, I bring you a tale of a video game series known only as Mafia. 2K Games released three installments between 2002 and 2016: Mafia: The City of Lost Heaven; Mafia II; and Mafia III. Depending on how you view the series, it’s either another welcome addition into the open-world genre, or yet another GTA clone, especially in era when that was all too common. And like the series, it may or may not be accused of ripping off along with other video games, the Mafia series draws from the inspiration of mobster media from Godfather to Goodfellas, but what sets it apart from GTA is that the satirical take on American society is nonexistent and the controversy that lingers over the GTA series like a noxious cloud is also nonexistent.

The focus in the games is based strictly on the Mafia and all the mobsters within, so while some characters may be inspired by someone like Bob Hope or Lauren Bacall or Tippi Hedren, the most you’ll get are throwaway lines of dialogue or even cinema boards advertising popular films from the era… which I count as a worldbuilding plus as it captures part of the atmosphere in the games, but I’ll explore that aspect later.

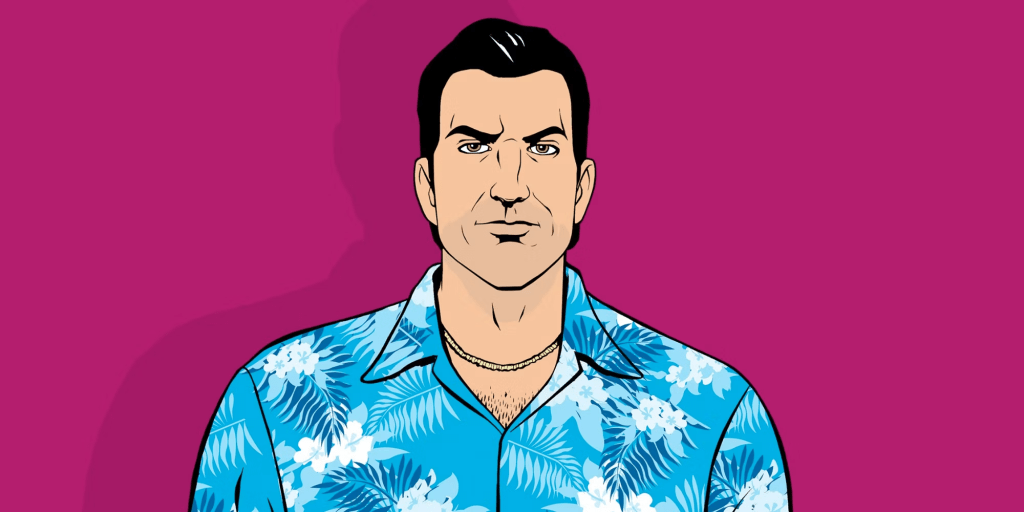

Mafia: The City of Lost Heaven (2002)

Set in the city of Lost Heaven, an amalgamation of several major midwestern cities (especially where the Purple Gang and Al Capone were based in), during the interwar period and Prohibition, cab driver Tommy Angelo is coerced into aiding and abetting mobsters Sam and Paulie into helping them escape a rival family. Already mafia material; on the way back to their territory, these members of the Salieri Family compensate him for the damages and buy his silence, which considering how corrupt law enforcement was at the time, may not have been necessary, then again, not everyone was eating bribes like beans on toast at the time.

Being given time to think about becoming a Salieri gangster himself, Tommy initially declines until the rival Morello gangsters wreck his car again, and attempt to break his legs. Now it’s a matter of survival; those f[aah!]kers were gonna eat him alive. Over the course of the rest of the ’30s, Tommy continues his work with the Mafia and learns firsthand how complicated things could get: enemies with connections, friends who want out, strict adherence to the laws of the Mafia, and even betrayal.

Compared to other open-world games, Mafia’s strength comes in its more grounded and serious portrayal as opposed to simply being a video game. It gets to be cinematic at times with Scorsese/Tarantino-esque set pieces and dialogue. The influence is strong enough that it can feel like any one of the movies it draws inspiration from. Lost Heaven’s setting was reflective of the time period. When the government passed the 21st Amendment in repeal of the 18th, they moved onto other profitable avenues of illicit activity. Hollywood had to get those drugs somehow…

Such a waste…

Incidentally, this won’t be the last time drugs make their way into the Mafia series. Lost Heaven seemingly ends on a high note, but just because Tommy’s tale is done doesn’t mean the consequences don’t find him later. Such as the case with real-life mobsters Abe Reles or Albert Anastasia. And where does he face these consequences?

Mafia II (2010):

In this game where the next protagonist, Sicilian immigrant, Vito Scaletta, takes the helm in the fictional Empire Bay, which may or may not be an amalgamation of a certain northeastern megalopolis. In all seriousness, the name immediately makes me think of New York, accents and all, but if I was a bit more well-traveled, I could probably make the case that Baltimore, Boston, and Dover are equally referenced too.

I haven’t seen any Silver or Golden Age films as of late, but one I do remember was 1933’s King Kong and all its primitive claymation ape suits, as well as 1932’s Scarface. Yeah, the 1983 one with Al Pacino is a remake of a classic. Bet you didn’t know that.

From what I remember of those films was the way the respective cities looked: the clothing, the buildings, the cars, the people and their accents, the outside world and its influence on the story–similarly, the case is felt in Mafia II. Vito says that his family moved when he was seven and he was born in 1925, which would mean he moved to the U.S. in 1932 before prohibition was repealed. He also claimed his father was an alcoholic who was probably also a frequent buyer of bootlegged booze until speakeasies were replaced by legitimate bars and taverns. Maybe some of the booze smuggled into the States made into his flask back east. Who knows?

Fast-forward to when Vito is 18, Japan had since roped the U.S. into a two-front war, and Vito’s gonna find himself on the frontlines after a robbery gone wrong. Drafted into the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (Currahee!), Vito is specially chosen as a native Italian for the U.S. combined effort to invade Europe through Sicily, for which his unit convenes with the Italian resistance. After guest-starring in HBO’s Band of Brothers for about two years, Vito returns to Empire Bay where his best friend, Joe Barbaro, has made a name for himself amongst the cities’ wiseguys.

Joe helps Vito avoid a redeployment, probably to Germany, by forging his papers, and find more work for him to do with the wiseguys, leading to crimes of a federal degree for which Vito was initially sentenced to a decade. However, thanks to even more wiseguys already serving sentences, Vito’s time behind bars is cut short and he’s released just in time to experience the early ’50s; where the mob was still going strong and official corruption was being virulently ignored long after the prohibition days.

Vito continues riding with the Mafia, reaching made man status, and reaching his highest of highs until, like Tommy Angelo, his past catches up to him and relatively quickly as well, leading to the loss of nearly all of his fancy belongings. Unlike Tommy who was forced into the Mafia out of survival, Vito did so to get riches. He worked so hard to stave off the poverty he lived through in those tenement homes and circumstances put him back at square one.

Admittedly more self-fulfilling than Tommy who definitely had his own qualms with Mafia life, Vito takes a bunch of jobs, one of which just so happens to include (spoilers) an attempt on Tommy’s life. Mafia II starts impersonal and gradually becomes more and more about Vito. He’s clearly not the first Italian to leave Italy and join the Mob in the U.S., but all things considered, he tried to solve his lack of money problem while also clearing a standing debt with a loan shark by dashing between odd jobs, but even if he wasn’t in debt, I still see Vito mad dashing to get the dough for himself.

Mafia II is divided into chapters and the first half has a lot of time in between them. The last half of the game though is spread out through a few days, probably the longest stretch between them being at most a week or close to it, obviously for narrative purposes, signifying what’s at stake: his life. Vito’s loose ends are finally tied, but in the end, the wiseguys who helped him in prison only vouched for him, not Joe who was there by coincidence. We the audience are lead to believe that he didn’t make it, but surprisingly, he and Vito eventually make their way to the third game’s setting…

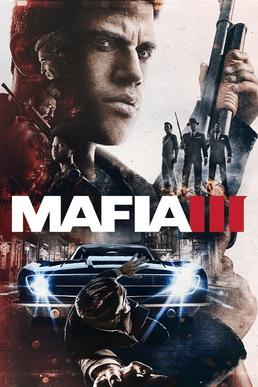

Mafia III (2016):

Now the setting is New Bordeaux, the game’s stand in for New Orleans, Louisiana and well within the civil rights era and counterculture movement of the late 1960s. This time the protagonist is an orphan named Lincoln Clay who by modern standards doesn’t meet the genealogical parameters to be considered black, having a Dominican mom and most likely Italian dad (whom fans theorized was Joe Barbaro himself), but going off face value (no pun intended), society put him into the black community who accepted him with open arms, even praying for his safety when he joined the Army and was sent to fight the Viet Cong.

His adoptive family is still there waiting for him, and he learns that they’re in trouble with a gang of Haitian descent while also being the “lapdogs” of the Italian Mafia in New Bordeaux. The antagonist, Sal Marcano, attempts to make an irrefusable offer which then gets refused and after one last job, Lincoln and his family are left for dead, setting him on a revenge quest. Continuing the theme of a living environment, the developers this time being Hangar 13 did well to capture the feeling of being non-white in the Deep South. Segregation ended federally in 1964, but the practice was still burning out years and even decades afterward, hence the the nearly 160 race riots across the U.S. in 1967, a lot of times in northern cities where segregation also existed but was outclassed by the southern way of separate but equal.

Lincoln Clay and the setting really distinguish Mafia III from the rest of the series with a brutally raw inclusion of racism as a mechanic, and it’s everywhere, from women clutching their personal bags whenever people of color walk by to stores having signs limiting or outright barring non-whites from entry and service.

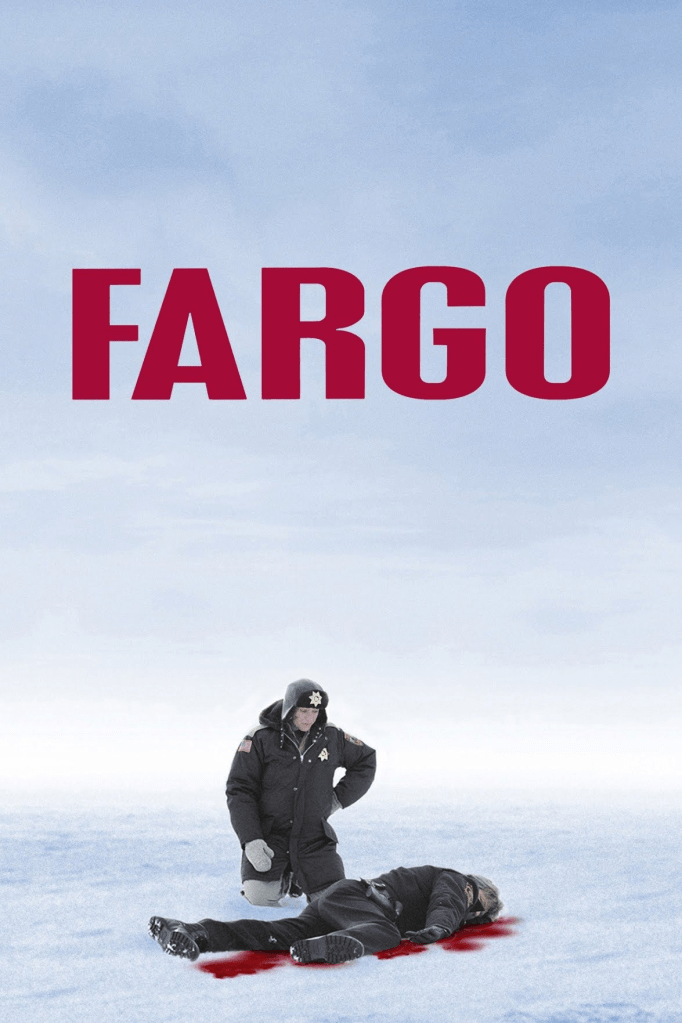

The story, not including all the DLC, had been terribly undercut by the mountains worth of technical glitches on release, but ignoring the initial release’s problems, I say the game does a great job of putting the player in the shoes of those who called that a reality back in the day. My grandmother, who grew up in Virginia in the ’40s and ’50s, has a bunch of corroborating stories from the era. It reminds me of the approach taking by Max Payne 3, making Max a private bodyguard for the wealthy in South America, isolating him linguistically as he traverses the many locales of São Paulo. You are the one nail that can’t be hammered in very easily.

From Prohibition to early Cold War to civil rights, the Mafia series had a momentous evolution. As of writing this, I’m 2/3s of the way through Mafia II and I’m still at the beginning of Mafia 2002 with plans to complete them both and the third one sometime in the future. In spite of all the faults in the games, I can’t recommend enough that you experience this trilogy at least once if you haven’t already.