The changes you notice when you’re in those boots too

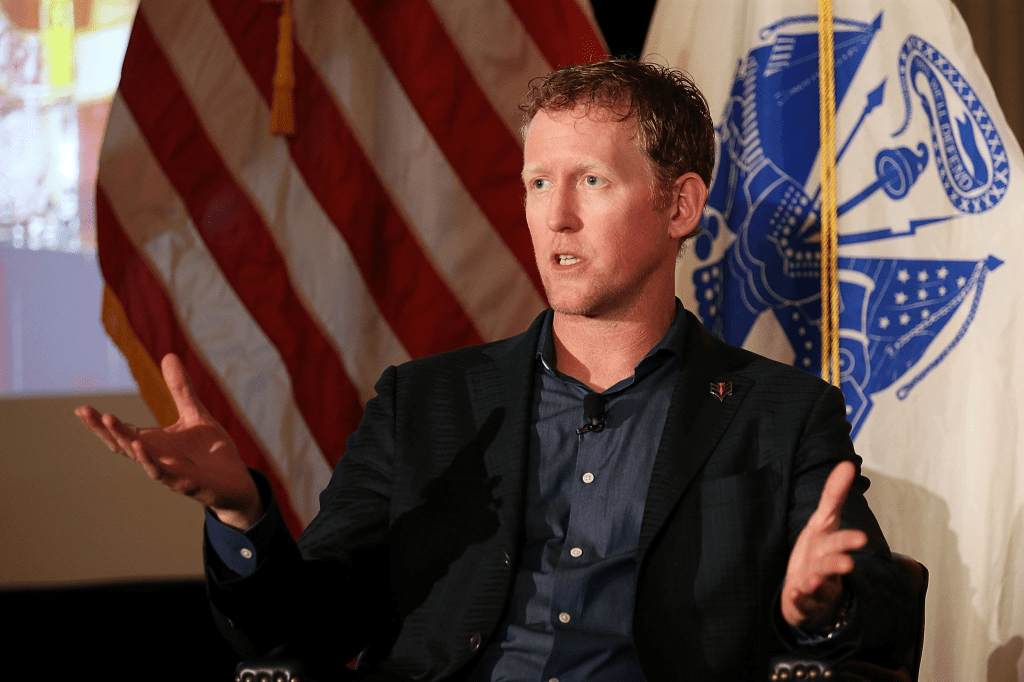

By now, regular viewers know that I’m currently in the U.S. Army, but if you’re just joining us: Hello, I run an entertainment-based blog during my free time in the Army. I do what I can to not make it my personality, and sometimes I’ll update you if it interferes with this blog (especially deployments and whatnot); occasionally, I add insight in my experiences in training whenever I see the military in media and the military shows up a handful of times in media.

Not the few times where they’re a side piece to the main event, but when they are the main event, and within the military and veteran communities, because of how we’re trained, the issues that fly over the heads of those who never served are all too obvious to those who have. I don’t normally go out of my way to hunt down military movies to watch; the most recent movie I saw was a touching love story about a man with a metallic skeleton traveling across the multiverse with his dumbest friend because they’re both too dangerous to be left alive.

All things considered, Deadpool is a menace to existence. Can’t wait to see him do it again with the web slinger.

Of the military movies I did see in recent memory were Black Hawk Down, Saving Private Ryan, and Full Metal Jacket, and I’ll go over them one by one based on what I know now that I’m in the Army. I’ve seen others, but these are the ones I can remember vividly.

Released in 2001, Black Hawk Down is a retelling of an actual event that happened to U.S. Soldiers overseas. For context, Somalia has a lot of the problems that were present in Afghanistan at least in the lead up to the Taliban’s first takeover in 1996. Post-colonialism was an opportunity for Cold War politicking and with Somalia and Ethiopia barking at each other, the U.S. and Soviets got involved. Glossing over the latter half of the Cold War in the Horn of Africa, the regimes changed, Somalia’s communist government was overthrown by an anticommunist government that was just as ruthless as the last and the most infamous man at the helm was warlord, Mohamed Farrah Aidid.

In the middle of the Somali Civil War which began at the end of the Cold War (no one can agree on a starting year, just that it’s still going on), one of the warlords Mohamed Farrah Aidid made a name for himself when those loyal to him attacked Pakistani military personnel in June 1993, followed by attacks on UN peacekeepers, prompting an American retaliation on his lieutenants. Aidid spat back by deliberately targeting American troops in the area, and the Clinton administration was done playing games, sending in Special Forces Group Delta and spearheading Operation Gothic Serpent with the sole purpose of bringing him to justice for crimes against humanity.

This was easier said than done and probably foreshadows the logistical issues of the later War on Terror which the Somali Civil War folded into down the line: who’s the enemy? The inciting incident that kept Delta Force in Mogadishu overnight in October 1993 was the downing of a pair of Black Hawk attack choppers. U.S. soldiers never leave a fallen comrade behind, so a garrison was tasked with finding the downed soldiers and bringing them home broken or in a box. It may be a trope these days, but we do take care of our own.

To put it mildly, U.S. soldiers were lost in a horror show even Satan would reject. Aidid’s paramilitary, the Somali National Alliance, wasn’t exactly a uniformed entity. The movie depicts them as dressed casually albeit adorned with military gear over their everyday attire, and scenes like this would come back to bite U.S. forces in the ass in the Middle East, especially in Iraq in the early years and after during the ISIS years.

The movie focuses mainly on the U.S. Army and its special forces contingents, but the reality was that more troops from other services (Navy SEALs and Air Force Parajumpers) were also involved. Those who survived the initial crash were trapped in the downed chopper, desperately awaiting help from other U.S. forces while the Somali population barreled down on them. Of the two Delta Force operators killed that day, Sergeants First Class Gary Gordon and Randy Shughart were the two who were given posthumous Medals of Honor. As for the rest of U.S. forces, the situation forced them to retreat with their fallen comrades in tow. Photos exist of what was done to the bodies afterward, but I’m not comfortable showing it. Just know that it was grizzly.

From what I’ve heard of people who’s family members served, those who were sent to Somalia would 9 out of 10 times rather be deployed literally anywhere else. Even Vietnam vets of the time, would rather fight the Viet Cong and NVA again than take their chances with Aidid’s forces again. Normally, I’d question the validity of these statements, but there’s enough evidence from retired servicemembers who were there to pretty much write it off as a living nightmare. Somalia is still a grave danger to residents and guests alike, but U.S. Special Forces are training Somali military units so that’s a silver lining.

The thing about the movie that stood out to me the most was a moment when Nelson and Twombly were left behind to cover for their unit while they headed to the crash site. Some time later, Yurek returns and presumably following their training, Twombly and Nelson fired until they realize it was another soldier. Yurek asks why they’re pulling security for a single deserted street corner where the two reveal that they were left there, assured that the rest of the unit would return shortly and that they have no radio or other means of communication because it was unnecessary.

Shortsighted orders are not unheard of at all in the military–in fact, it happens a lot. Military-based subreddits have members past and present sharing stories of commanders and senior enlisted leaders lying to themselves about the worst orders sent from the top down. Often they’re in a humorous light, but in the case of this scene in Black Hawk Down, a soldier stranded with no means of getting aid is above and beyond a blue falcon moment. Even if the unit didn’t know how long that rescue mission would take, leaving with just one radio would’ve been far better than deeming it unnecessary.

Overall, I can’t dispute the numbers. Critics liked it, audiences liked it, servicemembers talk about it, I liked it; inaccuracies exist about the finer details of the involved units, but isn’t enough to turn you off from the movie. It’s one of the good war movies. Give it a watch if you haven’t already.

Next is: Saving Private Ryan.

A classic 1998 war film about a platoon-sized element sent on a mission to find a sole survivor whose three other brothers perished at Normandy and send him home. Fun fact: when the movie debuted, it ignited a flurry of calls to the PTSD hotline because the Omaha landing scene triggered PTSD in veterans young and old.

The characters within this film are all fictional, but director Steven Spielberg relied on real-life accounts of families being drafted into World War II and losing brothers along the way. One such family whose sons were sent to Europe in the 1940s was that of the Niland brothers from Tonawanda, New York. Journalist Stephen Ambrose wrote of stories like those of the Niland brothers, and it wasn’t uncommon at the time for entire families of soldiers to get sent to combat. In World War I, for instance, Ike Sims, a former slave from Georgia, fathered 11 sons, all of whom died in combat.

The little details I noticed in Saving Private Ryan were numerous but the ones that stood out to me was when Corporal Reiben called attention for Captain Miller while in garrison, with Miller responding “as you were.” This is the rule for whenever an officer enters or exits a room. The troops stand at the position of attention and render a salute accompanied by the greeting of the day. The officer returns the salute and replies, “carry on,” to let the troops return to their previous activities.

Speaking of officers, while I’m not one, the rule of thumb that I know of with officers is that once they reach the rank of Major (Lieutenant Commander in the Navy and Coast Guard), they stop leading troops on the frontlines and work as battalion support, unless otherwise directed by higher-ups. I don’t know if that’s true, so don’t quote me on that. I just noticed that during the movie, more field-level officers are dressed in service uniforms than in combat/field uniforms. The exception is the lieutenant colonel who updates Miller on the situation and what he needs to do next, i.e. the plot of the movie.

There’s always praise to go around in a Spielberg flick, no matter how it turns out and while I did love this movie, there are criticisms or comments to make about it. It might be because of Spielberg’s professional background (with Schindler’s List under his belt), his religious upbringing, or the general portrayal of World War II as a black-and-white war, or all of these, but Saving Private Ryan can be viewed as a typical “saving the world” movie. Not that that’s a bad thing, but the reality on the ground was more complicated than western contemporary sources would have us believe. The Nazis had set up conscript battalions of nonethnic Germans in most of their occupied territories, feeding them the same old nationalistic manure to get them into the meat grinder. This was far more prevalent on the Eastern Front where there were more opponents of the Soviets than the Nazis until the war crimes were committed by both swastika and hammer and sickle standard-bearers, though I think Spielberg acknowledged this. It’s not an overall World War II film about stopping Hitler; it’s about a soldier who survived when his brothers gave their lives and is eventually sent back home.

Don’t let that discourage you from watching it if you haven’t already. You’re bound to have done so; Matt Damon aging five decades is a timeless meme for when you’re feeling old.

I put the template instead of an actual meme because I come across this one daily. Put your own spin on it; bonus points if it’s dark.

Lastly, is the movie that was supposed to decry war and the military, but ironically inspired more young men to sign up.

The most striking of this movie is that the character who would fill the role of Senior Drill Instructor Hartman wasn’t supposed to be R. Lee Ermey, but someone essentially coached by him. But looking at the final product, Ermey put the hat on once again and delivered a performance that’s been inspiring real and fictional servicemembers to this day. I’m pretty sure one of the senior drill sergeants from my basic at Fort Leonard Wood was in some way inspired by Ermey’s performance.

The first half is Marine Corps Boot Camp, and the second half is the characters in South Vietnam. The Marines are there own branch, and I don’t know what chicanery they get up to in boot camp, but it’s an extra month of training. Maybe if I find a Marine, I can ask, but I’m looking in from the outside for now. Being a Vietnam War-era film, it’s quite nuanced in some of the characters, the most famously nuanced character being Private Leonard Lawrence, i.e. Gomer Pyle. Knowing Better said it best when he said that Hollywood influences the military more than the other way around. Gomer Pyle was a satirical TV show from the 1960s, so every character in the film knows who DI Hartman is talking about, compared to my company at basic who might not know the origins of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C…. or funnily enough, Yogi Bear.

It’s a long story. Look up the “Yogi Bear is dead” marching cadence for context.

Other Hollywood characters regularly referenced in the movie is Mickey Mouse. Three little circles printing infinite money that Venezuela and Zimbabwe could’ve used when s[dial tone]t got flipped turned upside down.

For Leonard “Gomer Pyle” Lawrence, he’s a character who reflects a controversial policy launched by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Dubbed Project 100,000 or derisively as McNamara’s Morons or Misfits or Folly, the goal of the project was to bring the active duty troop number across the military from five to six figures in an effort to turn the tides of the war in the U.S.’s favor. This meant an aggressive draft that targeted the most disadvantaged in America, most notably those who would’ve suffered physically and/or mentally from training alone, let alone a combat deployment to South Vietnam. These ranged from the nearly mentally retarded to the high school dropouts to the literal illiterates with a 4th grade education.

Pvt. Pyle fits the category of McNamara’s Misfit to a T. He’s quite slow mentally, is about 150 pounds of chewed bubblegum, can barely understand the simplest of instructions until the entire platoon starts paying for his f[Attention!]k ups, and overall brings the platoon down, largely by accident. He struggles, yes, but he does try his best until he suffers a mental breakdown that leads to the death of both Hartman and himself in a murder-suicide.

The movie then cuts to Pvt.’s Cowboy and Joker in Vietnam, but in reality, an investigation would’ve been conducted. Different time or no, it’s not different enough where the service’s law enforcement agency wouldn’t investigate the death of both a drill instructor and a recruit. The predecessor to the modern Naval Criminal Investigative Service (then-called the Naval Investigative Service) would’ve questioned everyone about the incident and possibly divvied up the blame based on hazing. None of those Marines would’ve been sent to Vietnam. If charged and convicted of hazing, that’s turning in the olive greens in favor of prison denim or civilian clothing with barriers to re-entry. That, or barrier to promotion depending on how a JAG officer would like to see things. It does get the McNamara’s Folly part right that mass conscription of those deemed unfit would get mixed results at best. A lesson we swiftly forgot when it came time for the 2007 Iraq War troop surge if accounts from troops of the time are to be believed.

But whatever, Kubrick never served, he just directed the movie. The war part of the war film is something I don’t have experience with and–god-willing–it stays like that, but much of the film is essentially a repetition of the central “war is bad” message seen in insert work of art here. Even Saving Private Ryan is an antiwar movie with three out of four brothers going back in one piece.

I kinda pulled my punches selecting these movies for assessment only because I was sparing myself the disappointment that would come with other war/military movies that would get the military egregiously wrong. Sooner or later, I’ll bite the bullet and bring out the worst military movie I’ll have seen by then. Of the worst, The Hurt Locker is regularly decried and maligned by the veteran community.

I think I’ll watch it to see for myself.