Same continent, Different History

Full disclosure, the first topic lined up was meant to be about the Senran Kagura series, but I haven’t been playing it as much as of late. Work-related stuff among other things took my time, and for the style of gameplay, I’ve seen better. At least it has an anime adaptation. Next to that, was about a series that was subject to limited release outside of Japan — Idolmaster, only I’ve mentioned it before and without access to the whole of the franchise, I’m not able to review it in the manner I’d like. Typically, I start at the beginning, but the circumstances that created this series in particular are only available in Japanese arcades with the Xbox 360 port dying with the console, making the first installment in this franchise semi-lost media. So instead, we’re sticking with Nihon and talking about their movies.

As far as old movies go, whatever I could get my hands on I’d always given it a watch. In community college, I watched 1932’s Scarface and 1933’s King Kong. I managed to find the 1982 film The Wall based on the Pink Floyd album of the same name. I recommend all three by the way. And all of these plus similar films have been my go to for years, from my piracy era to my movie theater era. I’ve heard from the Extra History channel on YouTube in their series on Japanese Militarism that when it comes to studying societal changes in the Axis Countries during WWII, Germany and Italy get over-studied while Japan frustratingly has been under-studied or brushed aside, presumably because they don’t have an equivalent to Hitler and Mussolini, or rather no civilian equivalent with the Japanese military dragging the society down into Hell with them one assassinated politician at a time. I bring up the historical blind spot in an admittedly faulty comparison to my own approach to the Japanese film industry. I’m American, after all, my first movies are going to be American. Sometimes, British cinema will spillover.

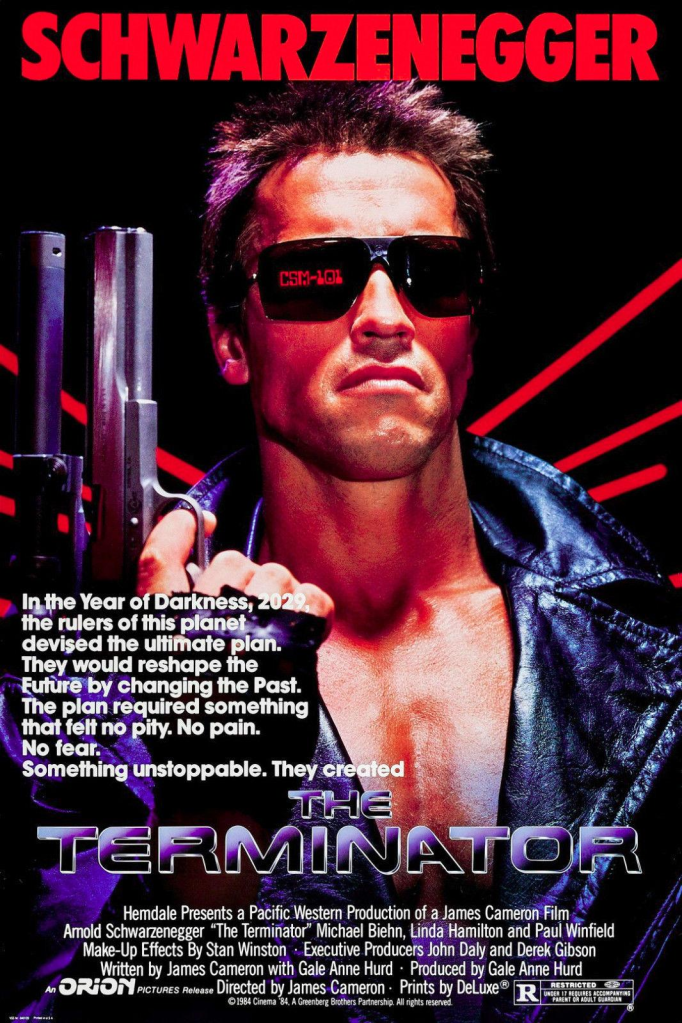

Guess I was always a sci-fi fan, I was just denying it because the genre was so broad.

Only recently have I been watching Japanese films and a lot of them are damn old, coming from legendary names in Japanese cinema, Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, and one other one I discovered whilst researching this topic, Kenji Mizoguchi. These three directors formed the foundation of post-WWII Japanese cinema in the 1950s during the Golden Age. By the time they were making film after film, Japan already had a storied cinematic history, though looking at the world the country left behind in and entered in favor of, one can see what kinds of films were being made especially during the late Taisho and early Showa periods. The short version of the history of the motion picture largely boils down to an amalgamation of centuries’ long efforts to get pictures to move by themselves, a means to record a moving flipbook and similarly, movements of this type popped up in East Asia.

Early films, as you can expect, are unimpressive considering what populates our screens, streaming services, and theaters today, but to Frederick Harrison Burgh in 1898, regular photos of the every man to his left and right were given life before his eyes. I didn’t exactly take any history of cinema courses, but I can also imagine a playwright of some kind looking at the first film directors in human history and incorporating the ideas into his plays or straight up becoming a film director himself in part or whole–to varying degrees of success. Maybe a combination of these, who knows?

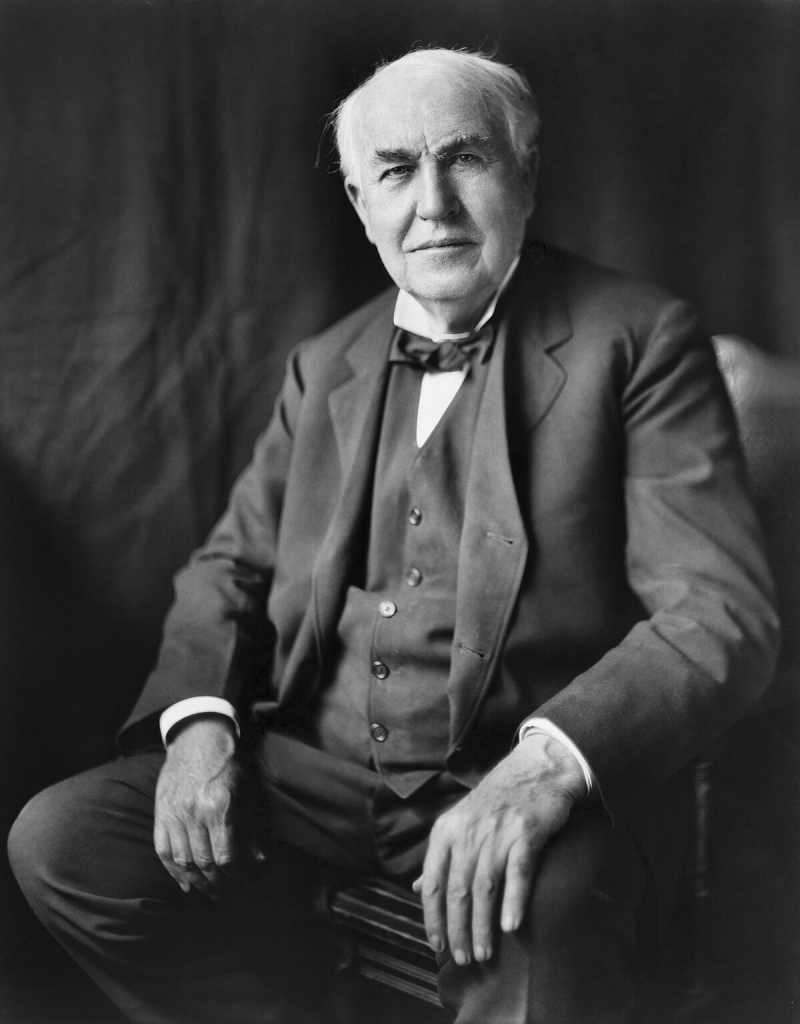

Even when Japan had more or less completed industrialization or neared its zenith, they weren’t done learning from western innovators, such as Thomas Edison.

Far from the progenitor of filmmaking, his inventions and contributions to cinema in particular formed the foundation of this industry worldwide. When the industry erupted in Japan, elements of kabuki and rakugo have made their way in over time. Narration, depictions of bygone eras, romanticism; different country, similar tropes about legendary figures. Just watch any western and compare it to the reality of the cowboy.

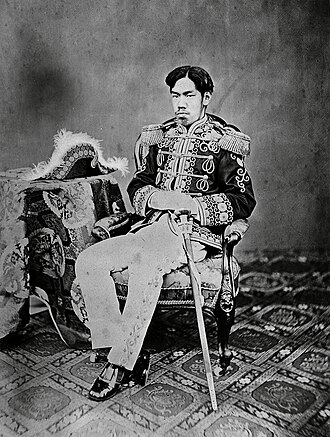

In this case, Japan had the shogunates and numerous tales of courageous warriors to adapt to film. Miyamoto Musashi, Tomoe Gozen, the main belligerents of the Genpei War; even the monarch has been depicted in film. Meiji was a fixture of post-WWII cinema for a time and looking at the Meiji era it’s easy to see why. A teenage emperor spearheads reforms that put an island nation on equal footing with the west over the course of about 45 years. Meiji was the emperor during the establishment of the Empire of Japan, his reforms reshaped the military into a powerhouse capable of knocking China and Russia around, empires many times the size of Japan itself and they were weak to Japanese might. Nationalist or no, you can’t help but laud an era of rapid industrialization and the man who helped with that.

These days, we can look at the era objectively, but the World Wars era emboldened and inspired filmmakers world wide. Wartime propaganda to motivate the populace to accept rations for the troops, instructional movies on the safety and operation of equipment and maneuvers, pre-mission briefs with the commanders in the war room before the march to battle: if done right, it can get the public firing on all cylinders and bolster the war effort significantly. If done wrong, the populace will be made complicit or forced to go along with the military’s worst actions. A tool of Japanese militarism, factions of junior officers in the Imperial Army and Navy formed individual groups all along the nationalist side of things. On the tame end, films released in this era in authoritarian nations helped lead to the cult of personality around certain authoritarians. Hitler had one, Mussolini had one, and I doubt he was aware of it, but Hirohito had a cult of personality as well, fostered by a radical faction working under the worst evolution of the national slogan, the latest one being “Revere the Emperor, Destroy the Traitors.”

The wild end of the propaganda spectrum can lead to the fabrication of enemies and dubious reasons to subjugate them. Most tools at their disposal were used for this purpose and led to ultimately dire consequences. Militarism could only last so long though and the dismantling of the Japanese colonial empire and subsequent occupation meant starting over again, with a new constitution and a self-defense industry with limited expeditionary capabilities.

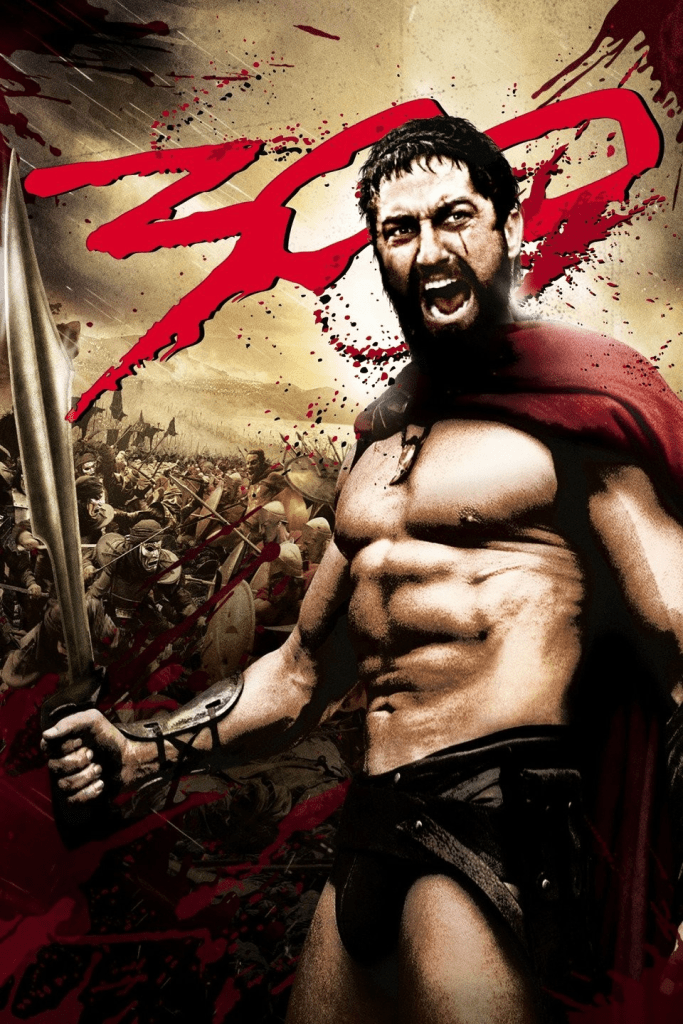

So where does filmmaking factor into all of this? Adaptable stories for one thing. Think of all the western films featuring Ancient Greece and Rome, even in a stylized/fictionalized manner.

Obviously, the Spartans had armor, these masters of warfare weren’t stupid.

As mentioned before, any knowledgeable filmmaker can make Japanese historical films, circling us back to the likes of Kurosawa, Ozu, and Mizoguchi. So far, I’ve only watched Kurosawa films, but I do want to talk about the others anyway. Kurosawa was an inspiration to many. He was to film what Osamu Tezuka was to animanga. The first time I watched him was in college during a course on Asian Art during the Japanese section. The film in question was called Ran and it was Kurosawa’s version of Shakespeare’s King Lear in a manner of speaking, which itself, when I saw it, drew parallels to the power struggle that emerged from the division of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century. All three stories involve a ruler of some kind who chooses to divide power among his heirs in near-equal status; all three fail to realize that the water of the womb doesn’t always bind and that siblings may bicker, but rich siblings don’t pull any punches; all three heirs immediately raise armies to rob the others of their territory; and all three explain in a gruesome showing why much of the known monarchic world defaulted to primogeniture. This model is criticized heavily by historians but without a better alternative, what were medieval kingdoms gonna do? Let a woman rule? Well, sometimes…

Queen Eleanor by Frederick Sandys, 1858

Remember when I mentioned western influence in Japan? Expanding beyond technology, this opens up a wider question on Japanese appeal to medieval Europe, of which the short answer to that is exoticism, same as how many westerners and weebs exoticize Japan and at times the rest of East Asia, hence why a lot of East Asian celebrities and such adopt western names.

Samurai tales were Kurosawa’s bread and butter and a great influence on samurai stories thereafter. One such film I had the pleasure to watch while on CQ was Yojimbo: the tale of an anti-hero ronin with a bullish demeanor who fights off gangs after getting to know an innkeeper family.

Moving onto Yasujiro Ozu’s output, he didn’t make samurai tales, instead favoring contemporary, slice of life films about everyday life. Exclusively Japanese life? Yes and no. Obviously, the setting is going to be in Japan, but the lifestyle of the people in his films being relatively modern make it relatable to many people globally. These aren’t disillusioned ex-samurai with a lot to gain in a changing Japan; these were regular people with commonfolk stories, easy to tell and far away from the realm of fantasy. I only recently discovered a few of Ozu’s films on the Internet Archive site, and I do plan on giving them all a proper viewing.

The last of the Golden Age Japanese directors is Kenji Mizoguchi, who I mentioned I discovered while drafting this post. Google and his Wikipedia page both tell me that his films historical dramas with a focus on women’s lives. How feministic! He was the oldest of the trio and being born when Meiji was still emperor and thus would have been exposed to the lives of not just female entertainers (geisha) but also of women going into a rapidly advancing Japan. This leads me to believe that, like much of the western world, Japan in particular was about to approach the subject of a woman’s place in life but not with the right approaches or interests at heart in mind. Or when the society did so, it was a mixed bag of controversial successes and failures. Like their male counterparts, women enjoy many of the same privileges enshrined in western societies, but some age-old challenges still linger, many of which became a central theme of Mizoguchi’s movies. Like most of the other media I have listed, I also plan to watch a few Mizoguchi films. I hadn’t made any concrete plans to write about them in any capacity, but I do wanna get back into it at some point–things have been looking a bit too anime otaku-centric as of late.

Not a shift, but an addition to my typical lineup.