A near-perfectly balanced dramady

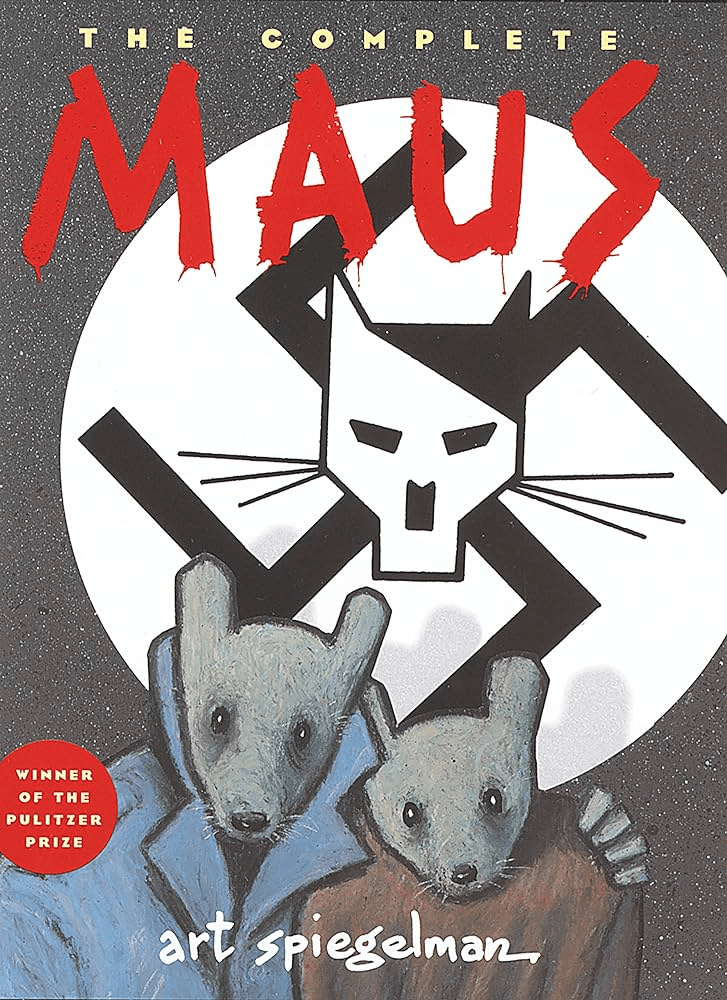

As both a history buff and a weeb, I like to think that history can work well even in graphic novel form. I’d bring proof, but so many political cartoons and, as mentioned before, graphic novels, have come out that the proof is everywhere you look. Here’s one of my favorite examples:

For the topic of this post (and something more lighthearted), I bring to you the manga series Golden Kamuy.

Created by Satoru Noda, Golden Kamuy is about a former Imperial Japanese soldier and Russo-Japanese war veteran named Saichi Sugimoto. After his military contract expires, Sugimoto hears from an ex-convict about a complicated story involving a legendary convict who hid a large stash of gold from the Ainu people of northern Japan, Hokkaido, and the Kuril Islands. When he was caught, he tattooed a map onto nearly 40 other convicts, each of whom is a specialist in his own right. After this, the prisoners were set to be relocated to another prison in the north of Japan, but the guards were ambushed and the convicts went into hiding. Sugimoto doesn’t buy into the story at first, but when the ex-con reveals that he’s one of the dozens tattooed by the legendary convict, he reveals the tattooist as “Noppera-bo.”

So far, we’ve got some interesting and familiar hooks, don’t we? A retired soldier searching for treasure, interactions with indigenous people groups, a changing political landscape, and slight spoilers for later, competing groups with similar interests. Almost sounds like a western… A story that fantastical would normally disappear into legend until you meet undeniable proof of its existence, but before we delve deeper into that, I want to discuss the historical background on which the manga is based.

Very briefly oversimplifying, Russo-Japanese relations in the early 20th century, the Russian and Japanese empires, both had conflicting interests in East Asia: for Russia, they wanted warm water ports and more land for the Trans-Siberian railway, and for Japan, they wanted to maintain political influence over East Asia, particularly Korea–but so did Russia. War broke out due to these conflicts and Russia maintaining a military presence in Manchuria when the original promise was for them to demobilize.

By 1905, the Theodore Roosevelt administration brokered a peace between the two powers that saw Japan as the victor, gaining the southern half of Sakhalin Island, political influence on the Korean peninsula, while Russia had to abandon its railway plans and its warm water port in Asia, the former of these later becoming Japan’s Southern Manchuria Railway which connected to that warm water port of Port Arthur.

Golden Kamuy is set in the aftermath of this. The fighting is long done away with, but the outside influences do have an impact on the characters. Keep in mind that decades before Japan went to blows with Russia, it was busy organizing itself into a modern country, and its first step was the reorganization of domestic territory into the modern day prefectures, all the while convincing the last of the samurai and feudal lords to surrender their holdings. Many did, but there were still a few holdouts, the most famous of them was the Vice Commander of the Shinsengumi, a hastily organized group of swordsmen with samurai sponsorship: Hijikata Toshizo.

This was all done during the Meiji Restoration of the 1860s. Although Golden Kamuy is decades after that, select characters with strong memories of the pre-Meiji days do still hang around. It’s also worth keeping in mind that the manga takes several liberties with history and some characters’ roles in specific events. Since I bring him up, Hijikata does appear in the manga, and is a part of a few flashback panels, but in the manga he appears as an old man and political prisoner since the Shinsengumi opposed the Meiji government. In real life, Hijikata Toshizo was shot dead on horseback while commanding troops in a major theatre of the Boshin War.

For the rest of the population of Japan, the Japanese government and media these days tend to promote an image of a homogenous populace, but reality is far different than what you’d believe. I briefly brought them up earlier, but the Ainu people are another central piece to the manga. The prisoner called “Noppera-bo” or “No Face” was the one who buried their gold in a hidden location and it takes the help of numerous Ainu peoples to help locate it. The Ainu people typically includes the indigenous groups found often in northern Japan and Hokkaido as mentioned before, but there are similar related groups elsewhere, on Sakhalin and in Russian Manchuria. These include but are not limited to the Uilta/Oroks, the Nivkh, the Nanai, and many more. One of these characters whom Sugimoto meets in Golden Kamuy is a little girl named Asirpa.

Asirpa serves as the audience’s window to an ethnic group that Japan has at best ignored and at worst disrespected. In history, the Yamato people of Japan gradually fought with them even into the Tokugawa Shogunate where they were forcefully relocated to Tohoku and Hokkaido. During the Meiji government in 1899, non-Japanese who were subjects of Japan (including the then-recently added Taiwan and soon to be added Korea) were forced to adopt Japanese names and use those publicly. True to this, even Asirpa has a Japanese name that would have to be used on official documents, as explained in her associated wiki page.

Nevertheless, love and appreciation for Ainu culture is evident and expressed in the Ainu characters, especially Asirpa when she explains language, naming customs, rituals, folk beliefs and several others. The name given to that convict who tattooed the map onto his fellow prisoners, Noppera-bo, is a reference to a Japanese spirit or “yokai.” The yokai come in a wide range of forms and depending on the legend, some are harmless or vicious. The Noppera-bo is described as a harmless yokai that takes the form of a human, only they have no face. Sorta like this:

Though as explained before, it normally takes the shape of a faceless human.

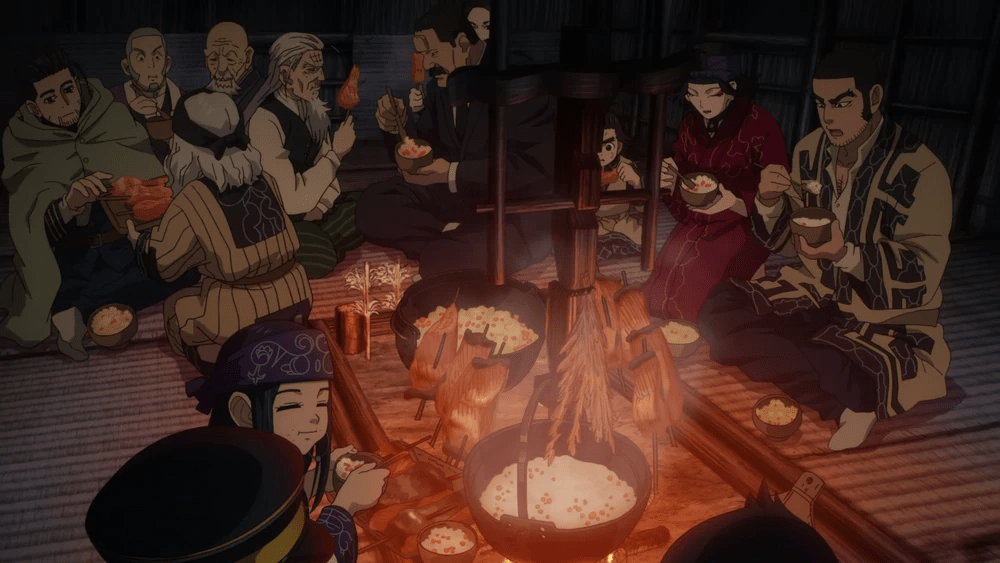

Regarding Ainu customs, the most famous aspect of the series among fans is the cuisine. It’s a common joke to refer to the series as a cooking show, which isn’t exactly inaccurate. Playing dodge bullet with loads of contentious groups is a key point of the series, but when there’s enough Arisaka rifle rounds flying for one scene, the next one transitions to Noda’s briefest possible tutorial on Ainu cooking, like so.

It may seem insignificant plot-wise considering where the story takes our main leads, but funny enough, there’s a healthy hosting of food scenes throughout the series. Noda explained that much of his experience comes from growing up in Hokkaido as an ethnic Japanese. The conceptualization and characterization of the Ainu in particular comes both from his own experiences, which he admitted were limited and from research, which there’s a lot of.

The characters as a whole are all varied more so in personality than in ethnic group, though there’s a couple of the latter such as the Matagi, or traditional winter hunters also in Tohoku, or even people with varied accents and dialects, notably Satsuma dialect.

Although Japan also promotes a singular dialect of Standard Japanese, there’s a variety of accents in the archipelago. Like the U.S. or U.K., there’s often different words for many of the same thing like soda, pop, or coke in many U.S. regions or what lunch in dinner are called in different parts of the U.K.

Personality wise, the characters all differ in what they want the Ainu gold for. Sugimoto made a promise with a wartime and childhood friend that he’d look after his wife who moved to the United States who was at risk of going blind. A mutinous faction of soldiers, led by 1st Lieutenant Tokushiro Tsurumi, a vengeful intelligence officer, wants the gold to fund a separatist state in Hokkaido to spite the Meiji government. Asirpa was influenced by her father and another Ainu character to also use the gold to separate the Ainu from Japan but for different reasons, and some characters never reveal the truth of their intentions with the gold.

For the most part, the characters are in some way based on real life characters from history. Some are obvious like Hijikata Toshizo living for another 40 years in this universe, and others require some more research to determine their inspirations. My favorite has to be the character Yoshitake Shiraishi who was based on the similarly named prisoner and escape artist, Yoshie Shiratori. Like his inspiration, Shiraishi is described as a master escape artist, finding creative and innovative ways to get out of a jam from contorting his joints to making false keys and using lockpicks. You’d probably need a rotating body of prison guards to keep him in place.

Between Shiraishi and Tsurumi, these characters are both unique and not unique. Their quirks make them stand out from regular background characters, but there’s a bunch of characters who match that description anyone. Sugimoto, for example, gained fame during the war as the Immortal Sugimoto and has thus carried this nomme de guerre in the civilian world. Tsurumi and select soldiers within his unit — 27th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division — are all quirky as well. One might describe it as a circus of sorts. And this is a similar case concerning the prisoners who carry the map on their bodies.

Just about everyone is a specialist in some singular skill or trade. This may make them one-trick ponies by themselves, but there’s a lot of moments where they get to shine independently or in mixed company. Asirpa, for one, may initially seem like a monolithic standard-bearer for the Ainu, especially since she’s introduced with an old and negative stereotype of indigenous people groups from westerns, but both her and the rest of the Ainu presented don’t seem to adhere fully to these misconceptions.

Similar to the Amerindians in the Americas, the Ainu and other people groups in North Asia would’ve spent their lives directly or indirectly interacting with non-indigenous folks, fighting, trading, working, befriending them among other things. They would’ve been exposed to foreign customs and technology sooner or later, hence why during the Manifest Destiny era of the U.S., bands and tribes of American Indians would have fought back with the same rifles that were being used on them. Off the battlefield, cooking and craftsmanship have also caught up with the times, so old depictions of indigenous folk as backwards and removed are just that: they’re old and quite inaccurate.

My introduction to the series came from some old Funimation ads in 2018. At the same time as my anime speedrun during college, bouncing between Crunchyroll, Funimation, and the now defunct VRV, the ads for then-recently adapted Golden Kamuy were showing and initially, I wasn’t that interested. Most people weren’t either. No matter how high the marks, the average viewer would’ve been looking for “time well spent.” This conflicts with the overall negative opinion of CG in anime and with most of the ads depicting Sugimoto’s battle with a CGI bear, prospective audiences were initially turned off.

Then I started watching in 2019 and continued to do so during the pandemic. My opinions on CG have been somewhat influenced by those expressed online, but in all honesty, if it looks good and it means the animators don’t have to crunch to get an episode out, then it can work well for an anime production, and I feel it does here. I honestly didn’t realize the bear was CG until a few frames in. Just goes to show how rare and at times apprehensive studios can be about integrating this technology into a production.

The manga concluded in April 2022, but the anime recently wrapped up it’s fourth season in June after taking a hiatus out of respect for a treasured cast member’s passing in November 2022. A fifth season is currently in development, though as of writing there’s no release date. This is ample time to go through the anime and then continue in the manga or start the manga and compare/contrast the anime. Whatever works best for you.

It’s a month divisible by 2, and the last of the year so as a final sendoff, December’s first YouTube recommendation gets to the heart of a topic I have in store for next week: Cynical Historian.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCN5mhhJYPcNUKBMZkR5Nfzg

The Cynical Historian is a YouTube channel that covers the history of the American Southwest primarily, and other topics in history secondarily. Started in March 2013, by former Army cavalry scout and noted historian Joseph Hall-Patton, the Cynical Historian has himself produced lessons and dissertations on his specialty in the American Southwest, namely violence and conflict, sometimes touching on the historicity of the local American Indian groups and figures active during the era. He runs a tight ship on his YouTube channel and has little tolerance for bigotry, hatred, or conspiracy theories of any kind.

One series he does that I recommend above all else is his Based on a True Story series that compares and contrasts historical moments and their silver screen depictions. Since the most recent video he did was in the lead up to the theatrical release of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon film, I suspect that a Based on a True Story video on the little corporal is somewhere in the pipeline, but without clairvoyance, I can’t say more. Be sure to check him out when you find the time.

Before I sign off proper, I had another video lined up emphasizing the surprising significance of food in Golden Kamuy, but couldn’t put it anywhere above, so I’ll link it down here.