Even more British than the GTA series

Although the GTA series routinely satirizes American culture from the safety and comfort of the same three locations–budget NYC, discount Miami, and dollar store Los Angeles, plus surrounding areas–the heart and soul of the series is Britain and there was an expansion pack for the original GTA, set in London and featuring James Bond of all people.

Not for nothing, I welcome more games set in the UK to break the mold for a change

But Rockstar North (formerly DMA Design) wasn’t the only British developer making open-world action games. Team SoHo, under the direction and storytelling prowess of Brendan McNamara, the same one who practically drove Team Bondi into a shallow grave, released The Getaway in December 2002 in Europe and Oceania, and in 2003 in North America; in a rare instance of Europe getting the game before America and Canada. Not so much a parody of the setting, the nature of the game was intended for a cinematic experience, so the comparisons to draw between itself, GTA, and the True Crime series all fall rather flat by way of the UI design.

From a technical standpoint, it’s a very unorthodox open-world game. Set in the borough of the City of London, not to be confused with Greater London as the PS2 never had that kind of power to render a whole f[traffic]ng city, the UI is sans a HUD, so you don’t see a typical health bar for the character. Rather, the damage is reflected on the character’s body itself, so think of any open-world game with the damage to match, but it actually had an effect on the character instead of just being a porous open wound treated the same as a scratch or a bug bite. Too many shots to center mass before death leave you huffing and heaving for mercy at which point you simply lean against a nearby wall and you’re back in action. You also don’t have a way to count your bullets unless you’re whispering the number of shots taken to yourself, but without Senku Ishigami’s brain, you’re bound to be inaccurate. Fortunately, it has what it took GTA and Max Payne ages to implement. A cover system! But it conflicts with the camera sometimes, so good luck making your targets before your carotid artery gets blocked by a loose bullet.

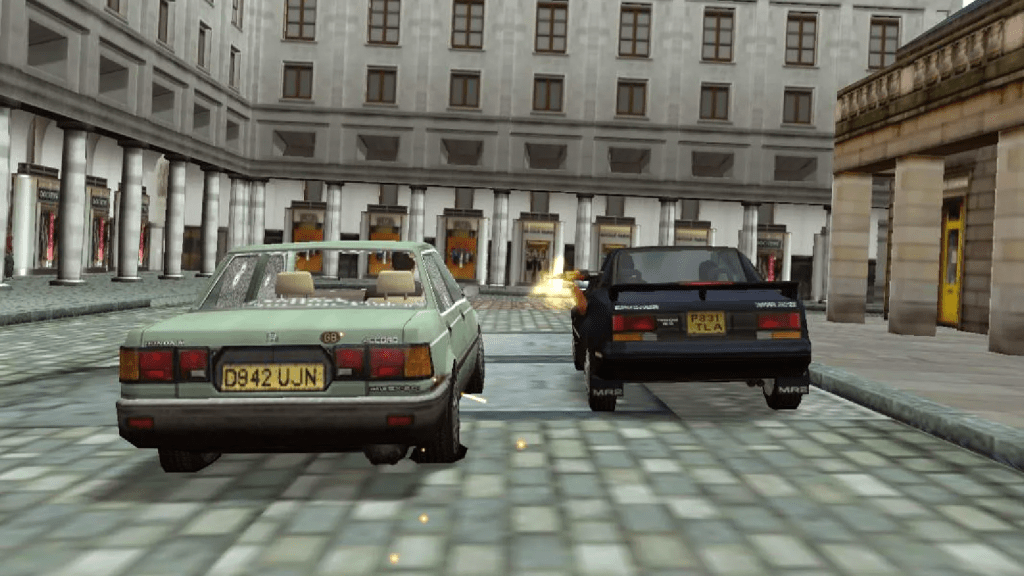

How about driving? Are there any arrows or a map that can help me navigate? Nope. You’re vehicular navigation is handled by way of the turn signals, and on the one hand; f[beeping]ng yes, the one game where they serve a purpose. But on the other hand; without a good map of the City of London, or any sense of familiarity, I feel even more like a tourist to Britain than I would be in real life. Turn signals being an extremely rare thing to see being used in any kind of video game is a novel idea that I wish was more common in games these days, however the implementation here is to direct you to your destination. The lights flashing faster when you’re on the street you need to turn into and the hazard lights popping on once you’re there. Additionally, the cars this time around come from real-life brands as opposed to some Frankenstein creation of existing brands that Rockstar has always loved, so you get to drive an RHD Honda or a Lexus or a Vauxhall if you care very much about that sort of thing.

For personal research, I looked up a bunch of the manufacturers and most of the car companies have since gone out of business, been absorbed in consolidation efforts, or their parent companies decided to focus on what they were originally good at, as is the case with Saab to an extent.

So what’s the game about? It starts with a woman getting gunned down and her son kidnapped by gangsters working for a crooked geezer named Charlie Jolson. Jolson ordered this attack to force the protagonist of the story, Mark Hammond, to be his personal slave and run all over the borough kicking s[tire screech]t up and causing conflict between the cities gangs of which there are four: Jolson’s gang known as the Bethnal Green Mob, Hammond’s former gang known as the Collins gang, the 14K Triads, and the Yardies. Jolson himself is particularly dastardly, aligning himself with the far-right National Front movement in Britain. For those who don’t know, the National Front in the UK has a reputation as a neo-Nazi, white supremacist political movement, and is one of several far-right political parties and/or movements from the UK, so making Jolson a member of this group can feel like forced hatred of a character to some, but I can easily see someone putting him in the same light as Battle Tendency’s Rudol von Stroheim. I wouldn’t be surprised if Jolson’s ill-gotten gains were a means of quietly funding far-right individuals to steer Britain in a neo-fascist direction.

Jolson’s main enemies, aside from Hammond, is Hammond’s original crew, the Collins gang, founded by Nick Collins. It’s explained in the story that Hammond was a part of this crew until he got pinched in 1997. Since his release in 2002 he vowed to stay on the straight and narrow until the powers that be forced him back into the life. The third gang you antagonize is the infamous 14K Triad group, who are generally more powerful in China and their territories, but also have influence over sections of the diaspora, even in the UK.

Lastly, there’s the Yardies, an umbrella term for any Jamaican organized crime group, typically used interchangeably with the term for “posse.” Like their triad counterparts, they’re generally more powerful in Kingston and Spanish Town, but have a roof over the heads of sections of the diaspora, with overseas Jamaicans calling Britain, America, Canada, and the rest of the West Indies home.

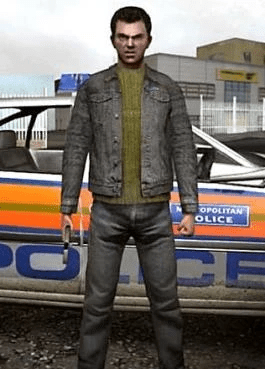

The main plot of the game is let Jolson step all over you and earn a chance to get your son back, but it also subdivides into a different focus and brings on another protagonist, Frank Carter, the undercover cop and Britain’s answer to Dirty Harry, stopping at nothing until Jolson and his kind are dead or imprisoned. Maybe both.

I’m not entirely sure how long the game is, but I know I’m about a third or so into Hammond’s part of the story. I’m trying not to spoil myself too much and keep as much of it a surprise as I can. For the gameplay aspect, there’s some variation to the movement on foot and in a car, and even shooting has quite a bit of variance. Without a HUD, the game employs much of the same mechanics of weapon equipment found in later, fancier titles like Max Payne 3 or Red Dead Redemption 2, only you get the impression that Hammond doesn’t give much of a toss over what he has on hand, with the plot reflecting that he’s only doing all this s[clank]t because Jolson is threatening to kill Hammond’s kid. But it’s not like he’s completely enslaved to the prick; one of Hammond’s best mates, Liam Spencer, hears about what’s going on and helps Hammond get one over on Jolson.

If I had to wager a guess for the rest of the game, I take it Hammond attempts to find his son himself, but gets caught up and has to suffer the wrath of Jolson’s boys, leading to the switch up to Carter.

The Wiki makes him sound like a loose cannon and I have until I get to his part to confirm that

These days, The Getaway is more than a little bit rough around the edges, but it’s not like GTA III levels of difficult. Personally, it could benefit from a modern remake with more responsive controls not dissimilar to what Sega did with the Kiwami remakes of the Yakuza/Like a Dragon PS2 games. But it did gangbusters at the time and was able to produce a sequel subtitled Black Monday in 2004, and a PSP exclusive called Gangs of London in 2006.

A third mainline installment was supposed to release sometime after 2008 on PS3, but the project was cancelled alongside another unrelated game called Eight Days, or according to the devs at the time, the games were put “on hold.” But considering it’s been nearly 20 years since either of the games have been in the public consciousness, I highly doubt anyone is holding out for either game to finish development after so f[goat bleats]ng long. The same thing goes for Beyond Good and Evil 2 and any hope anyone had for a third installment of a Valve game.

I don’t know why I suddenly wanted to bully this game, I don’t really have a reason to. I just popped into my head one day as that thing that’s been in development hell for ages.

For what it’s worth though, Team SoHo’s brainchild inspired by British gangster flicks went on to embed itself in British gangster media years down the line with a spinoff TV series in 2020 and a graphic novel two years later. Unlike Yakuza though, I don’t think I’ll see myself going through the whole of the franchise. Tracking down games to emulate is becoming a chore over time–this would be so much worse. I still wanna consume more foreign media and I think I have a case for another location:

I already saw the Tropa de Elite movies, and I know there’s more to discover outside of telenovelas. I’m gonna make this a goal for the year.