More unsung manga recs

Back into the fold with a manga that I genuinely tried to research reviews for but this time I came up short. Google helps with pages of individual reviews on different sites, but video reviews are what’s lacking. A quick search on YouTube (as of this writing) brings me to about seven or eight videos that don’t really have a great audience number collectively, only a few cracking a thousand views, at least on English YouTube; Japanese YT has more to talk about it seems. On the one hand, I want to see that change, but on the other hand, the subject matter of what I’m about to talk about in this post may highlight why this is for the best.

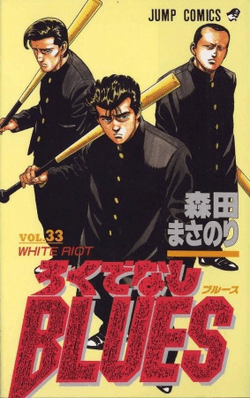

The manga I bring to you is called Rokudenashi Blues, known alternatively as Good For Nothing Blues.

I’ve made a small mention of this manga in earlier post (can’t remember which one), but here I’d like to elaborate on what it’s about. Created by Masanori Morita, it ran from May 1988 to February 1997 in Shueisha, spawned several OVAs, a couple of films and TV dramas with the most recent one listed having run for the summer of 2011 in Japan on the Nippon TV network.

It’s about a highschooler named Taison Maeda, a bullheaded delinquent who dreams of becoming a world-class boxer, racking up a gnarly fight count along the way. In Japan from around the late 1970s to the early 90s, the delinquent subculture is more of a lifestyle than an indicator of anything more sinister; it’s not like Japanese delinquents have ties to the Yakuza or anything else organized crime-like. Some do or did, but they’d be the outlier, not the standard. For an idea of what a delinquent is in media, look no further than Jotaro Kujo or Yusuke Urameshi.

The first discernable aspect of the delinquent is to compare them to any other student. The delinquent’s hair is loose, long, messy, or sometimes combed into a pompadour; their uniforms are loose-fitting and scruffy with unfastened buttons, and in some cases they’re elaborately decorated with kanji or any other lettering or symbolism. I’m not sure if there’s a meaning behind it; some depictions I can see relate to luck or strength, so that might be a theme with select individuals who partake.

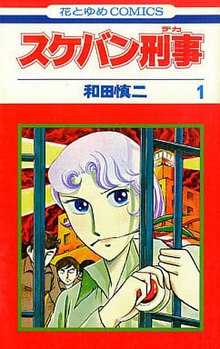

It should also be highlighted that it wasn’t exclusively a boys thing to engage in delinquent culture — girls did it too. In contrast with their more studious counterparts, girl delinquents, or sukeban, wore longer skirts, down to the ankle, and also tended to have their hair as messy as their male counterparts. Of all the examples of a sukeban in media, the best example comes from the movie Sukeban Deka, a Shoujo manga that has climbed to popularity thanks to its live-action adaptation.

If this aesthetic looks familiar, there was a bit of a crossover between the greasers of the 1950s in the US and the punks of the 70s and 80s in the US, UK, and Australia. So keep this in mind when you come across Japanese media from the 80s or 90s; it’s a classic. Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, delinquents have fallen to the wayside while gyarus and by extension the kogal has taken over with media featuring the subculture still slated for release in the near future.

But I think nostalgia will either bring the delinquent back, or put the archetype side-by-side with the gyaru.

In Rokudenashi Blues, the protagonist Maeda and at times his friends, Katsuji and Yoneji clash with rivals first within the school and then in different parts of the Tokyo Metropolis as the series progresses, sort of like the huge fight between different middle schools in Mob Psycho 100.

The clashes with these numbskulls are weekly, if not daily, and the popularity of the delinquent’s outfit makes it easy to lose among the scuffle, but in both a character design and personality sense, there’s a few that stand out from the mold: Wajima and Hatanaka.

Wajima’s designed to be a physically imposing character. Think of your typical brawler or weightlifter body type from a beat ’em up video game. He leads one of the groups known as the Cheer Squad in the school and these guys have fought with Maeda and co. at times. Personality-wise, he’s as bullheaded and shortsighted as Maeda, at least in the beginning. I’m still reading the manga so it remains to be seen how he grows as a character.

Another one who mirrors Maeda in looks, but succeeds him in overall intelligence would be Yutaro Hatanaka. These two have clashing goals and in classic Shonen Jump fashion, he’s set up as the rival to Maeda, but unlike him, Hatanaka has a clear plan that he can recite with steps toward his final goal. Basically, what I’m saying is, he seems to be more studious and articulate with his thoughts, though when it’s time to play rough he can do it in stride. He’s a bit like Sasuke though far less brooding and more laidback compared to the energetic Maeda. It also remains to be seen how he grows over the course of the manga. I have a few ideas on the trajectory, but I want to see the surprise for myself.

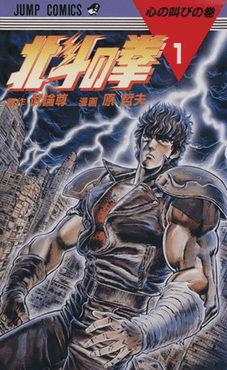

The art style of the manga may also be familiar to fans of Fist of the North Star/Hokuto no Ken, and the reason for that is because the mangaka, Masanori Morita, previously worked as an assistant for the creator of Fist of the North Star, Tetsuo Hara.

This art style became the face of 1980s action manga with several mangaka taking elements from Hara’s magnum opus. It was a ground breaking inspiration for many creators over the years and according to some accounts serves as the main inspiration for characters like Jonathan Joestar and Dio Brando. Several more characters of this caliber would follow over the years, but it’s hard to say how many were developed in a vacuum or took on the shape of Kenshiro in some capacity.

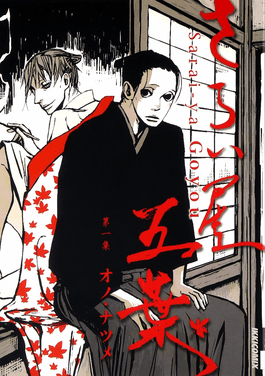

I stumbled upon this manga after I remembered an article that mentioned other underrated series a few years ago and went to explore some of those suggestions for myself. In fact, on another blog, I talked about one of those series after watching it from start to finish on YouTube; it was the series House of Five Leaves/Sarai-ya Go You by Natsume Ono.

I plan on redoing it on this blog one day as I wasn’t all that proud of what I said in the last one.

Even if you’re not one for boxing or sports in general, I still give Rokudenashi Blues a solid recommendation. It’s got a lot of heart and it’s not exactly the most complex sports manga ever, but the manga focuses more so on the characters and their lives as they go (read: brawl) through school and later, as I’ve been told, through other schools. I may return with an update once I’m finished with the manga, though that’s not a fixed and consistent schedule so it remains to be seen.

[…] or titles you’ve never heard of until recently, either through me or another medium. This continues the trend I started here from 2023 and continues to be a personal crusade of mine. Not limited to Shonen […]

LikeLike