The God of War protagonist is one of the least understood characters in gaming.

In November of 2022, the rebooted God of War series released its next installment with God of War: Ragnarok. I have yet to play it or its predecessor myself as I’d been holding out for years to get my hands on a PS4 to play it appropriately, although God of War 4 was rereleased for PC last January. As a result, I’ve been getting snippets of the reboot game and try my best to avoid spoilers for Ragnarok, considering a huge spoiler revealed in the preceding one.

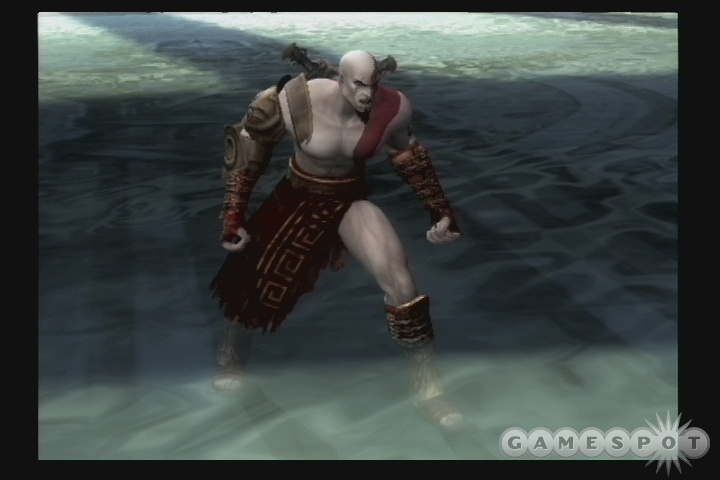

But we aren’t going to talk about Norse saga Kratos. I want to talk about Greek saga Kratos and the many ways in which he is severely misunderstood. Some of this will come from the games themselves, some more of this analysis will be from critics, and the rest will take the piss out of those with short attention spans, though that Venn diagram at times feels more like a flat circle.

Greek Kratos deserves a retro-analysis. In brief, he was a very patriotic Spartan commander who willingly devoted himself to the god of war Ares for the sake of glory and conquest. This extreme devotion necessitated the deaths of thousands of innocents and only ceases when a cryptic oracle warns that his final victims will haunt him all his days. Accidentally killing his wife Lysandra and their daughter Calliope, the ashes of his family become fastened to his skin for good.

In penance, Kratos serves the gods of Mt. Olympus in the gradually vain hope that they’ll free him of the nightmares of that awful night. Although they shower him with seemingly related treasures, the power to forget will almost never be with him again as the events of that fateful night never leave him. Tired of this, Kratos sought to topple the King of Olympus, Zeus for denying him this one single wish.

Based on that description, it can be assumed that Kratos is a victim of divine machinations. If you know anything about Greek tragedy and mythology, this doesn’t make Kratos unique in any way. The cast of the Trojan War, Ajax, Heracles, Perseus; all of these heroes and/or demigods go through the foulest depths of Hades either at the behest of Olympus, for redemption, or something else entirely. Their fates are pre-written by oracles who are themselves eternal victims of the hero’s pride and aloofness. No one adheres the oracle until it’s too late.

In the case of Kratos, his fate matches that of Heracles in all but presentation. This is due to the games either explaining poorly how the events of that night went down or Kratos himself making himself feel less complicit to alleviate the guilt, but the bottom line is that he committed an awful sin that changed his life for the worst and accepting the consequences of that he chooses to atone for his sins the hard way instead of waste his effort trying to return his loved ones to him.

Overall, I’d say this is presented quite well in the games bar a few retcons from the PSP exclusives in Chains of Olympus and Ghost of Sparta. However, when God of War III was released in March of 2010, countless journalists and audience members have changed the nature of the conversation around the man.

Prior to the release of this game, it’s possible a more intellectual conversation could be an examination of his character within the lens of Greek tragedy. Now that God of War 4 has muted his character and reminded the player of what he used to be, most people look back on Greek Kratos with disdain and disappointment, writing him off as a creature more heartless than the ones he slew in battle.

As a matter of fact, God of War 4 outsold the previous games by tens of millions and with this one being most players introduction to the series these days, the complexities of the original Kratos are bound to fall on deaf ears and blind eyes. To be fair, I’m not saying its bad to like or prefer Norse Kratos to Greek Kratos. The YouTuber Tactical Bacon Productions has an interesting description of the two; in his words, Kratos is a bit like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Either condiment can work great independently or in tandem. Additionally, both versions of Kratos are heavily layered, like a tequila sunrise.

Across the original six Greek saga games and the two lengthy Norse saga games, Kratos is far from a simple character. If the Greek saga is written like a tragedy, I would like to believe that the snippets of the Norse saga I’ve seen take from Snorri Sturluson’s probable contributions to the Prose Edda in Norse mythos. What this means is these works have incorporated aspects of the behaviors of the societies within into the writing. Greek Kratos didn’t behave the same way as Superman or Batman, and Norse Kratos (based on how he engages other characters in God of War 4 alone) takes after the likes of Beowulf, if you think about it.

Heroes back then didn’t exclusively save people. Them deceiving people or killing with reckless abandon would make them antiheroes today, but in a more violent age where people weren’t guaranteed senior citizenry, violence was as second nature as breathing. And these were the times Kratos grew up in. You can argue that him being a Spartan is why he’s inhumanly brutal, but even outside of Sparta, neighboring Greek city-states were quite harsh on their people, especially their militaries. Sparta is special in how they did most things.

Sparta’s militarism traveled far and wide to the point that they would rank pretty high in a Top 10 list of toughest militaries. The system of agoge meant that young Spartan boys would learn, grow up, and expect to die for the city-state in battle. For Kratos, there’s no greater source of respect than being a battle-hardened veteran. He’s learned to respect active duty soldiers and elderly veterans. From his fellow Spartans to King Leonidas to even God of War II’s depiction of Theseus. In fact, the latter of those three was one of the few Kratos didn’t immediately trounce on. Him being an elderly though still agile warrior was why Kratos spoke to him with a modicum of respect with a little jab thrown in. Like a War on Terror vet speaking with a World War II or Korean War veteran. Both guys know what it’s like to serve, and are almost guaranteed to break each other’s balls.

Admittedly, Kratos is a product of his homeland. Additionally, he has a long history as first a soldier a Sparta and later a servant of Ares before he felt betrayed by the god of war.

Actually, there’s a misconception about Kratos’ mission to kill Ares as well. God of War 2005 feeds the player piecemeal by explaining that Kratos’ bloodlust on the battlefield was a possible side effect of pledging himself to Ares for survival. In Ascension, it explains that there was a triplicate’s worth of blood for him to spill under Ares and with the Blades of Chaos: the blood of the innocent, the blood of his enemies, and the blood of his family.

Ares’ sole devotee was groomed to be the best warrior in existence, but he didn’t account for (or perhaps did) his greatest warrior being great enough to unseat the god of war himself the hard way. But he didn’t merely do it for himself. If he did, he wouldn’t have spent a decade atoning for this awful sin for the gods. If he really thought he could slay Ares off the bat, would he waste ten years trying to forget he was the Apostle of Battle? Ascension is spent explaining what it took to be free of Ares control. And Chains of Olympus barely features the rogue god in name or in depiction, but him still being an active Olympian in the timeline means he’s going to put up with the gods even when his patience begins to wear thin.

But if we’re sticking with the trilogy and nothing else, you can find more instances of Kratos questioning his abilities despite the incredible things he does. Then again, him possessing abilities most folks lack like super strength, resilience, and the ability to will himself back to life are oddly ordinary to him. He’s technically the first person to try and kill a god, something unthinkable before he was tasked with doing so. And that’s the distinction — he was specifically tasked by Olympus to kill Ares and by extension restore order, and he wasn’t asking for much in return. The nightmares and advanced PTSD make sleeping near-impossible for the Ghost of Sparta, and no matter how many times he asks to forget, Zeus and Olympus have always said no.

Going back to the spin offs for a bit, a throwaway line between Kratos and the Grave Digger (Zeus in disguise) in Ghost of Sparta reveals what he thinks about being given Ares’ place on Olympus. A consolation prize that doesn’t do what it’s supposed to. He’s not thrilled about being the god of war. It isn’t until the end of Ghost of Sparta and the beginning of the second game that being a war god has its uses. Years of empty promises from Olympus motivate an extremely drastic reaction that starts the end of the saga with him riding the back of Gaia as she and the titans who were defeated in the Titanomachy scale Mt. Olympus and openly battle the Olympians.

Still, minor moments in the last of the trilogy were bound to be taken out of isolation for the brutality therein. Brutal or not, there’s a larger discussion to be had about the game, that being “why is one of Zeus’ bastard children toppling and terrorizing the home of the gods?”

If the gods weren’t so up their own ass about addressing this one man’s sole desire, then perhaps he wouldn’t have had to prove his atheism so hard. And if you just read that and thought to yourself, “how can he be an atheist when gods are real in this universe?” Motherfucker, who do you think is the progenitor? First to kill a god, first to be made a major god, first to reject his own godhood and drag the whole pantheon down with him… need I say more?

All in all, it was Zeus denying him a simple wish that accelerated his path to monstrosity. Does this mean his path was inevitable? Not really. I actually believe Kratos’ entire life would be different if he didn’t bother to involve himself with the gods and vice versa. Sure, his and his brother Deimos’ father would likely remain a mystery until the end of days, but part of me thinks there’s a scenario where he and Deimos take turns caring for their sickly mother Callisto while routinely returning from campaigns of battle to shower Lysandra and Calliope with trinkets taken from other lands. But that’s just my headcanon.

If you play the games in a certain order, you see him go from “what have I become?” to “I bring the destruction of Olympus.” It’s a well-written, and complex story arc. It’s a bit like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This manufactured monster destroyed his own creator. But above that, his immediate family tends to suffer along with him due to the gods or because of his actions in relation to the gods. Time after time, he willingly stays his arms for his family, makes sacrifices for them or apparitions of them only to lose them shortly thereafter. Most of the time, it isn’t real, but for a guy whose mind is plagued by nightmares of his family, being reminded of your sins by wearing that reminder as your skin is harsh. Imagining them in death for the umpteenth time would make anyone stark raving mad.

While Kratos has zero chill, Zeus and the Olympians making things worse does no one any favors. And this is what needs to be considered when examining Kratos’ character. Everything that’s happened to him is what drives his rampage at the end of the Greek saga. Can a character have no depth when they willingly throw themselves to the underworld for the sake of a loved one?

I’m using the power of hearts, stars, and horseshoes for this, but if the general gaming public and gaming journalism bothers to re-analyze Kratos’ character, both from the context of how Greek tragedies were written and everything that led up to his crusade across the old games, then maybe the false idea that Norse Kratos is the more mature and therefore better version of the character would perhaps be put to rest, which does him far better than what the gods have been doing with him all these years.

Do away with isolating shocking moments. Stop thinking there’s no connection between the deaths of the Furies and Ares. Stop and think about why Kratos did what he did.