About time I addressed a noticeable pattern of mine

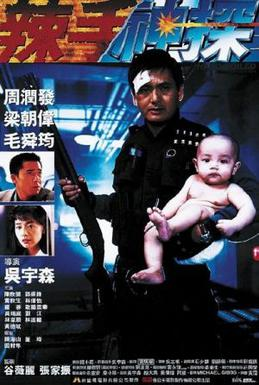

Between Hong Kong cinematic action pieces of yesteryear and Japan’s golden age of cinema, I’ve been quite busy exploring the directors of East Asia. So far, I’ve addressed four powerful names in the cinematic world (John Woo, Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi), but this is only the tip of the iceberg, as I’ve definitely seen more than just those for in both the live-action and animated worlds. And before I expand on that, I thought I’d address that for a few seconds:

I love this era of literal memes, it beats brainrot 100% of the time.

The archives of this very blog show that the things I write the most about animanga and almost always on the series itself as opposed to the production side of things. It’s been this way since the blog first launched in 2023 and when it comes to writing about the production side, it’s heavily skewed toward games, movies and TV series. The reasons for this have to do with what creators are willing to share to news agencies. From my experience, game devs are happy to document the process from storyboard to controller to thrown off a cliff by Margit the Fell Omen.

Animanga is a lot of the same but it highly depends on the publisher. So while the 3D Mortal Kombat games have videos where Ed Boon et al talk candidly on the creation and re-introduction of legacy MK characters, Francis Ford Coppola feels cathartic talking about the troubles facing Apocalypse Now, and Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul would walk you through the making of Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, only a few manga publishers I’ve found are to be this open about their processes. Individual mangaka certainly, but editors for companies like Shueisha, Kadokawa, etc. are more than a little lockjawed. Even when they do show journalists the tour or sit down to conduct an interview, the details are either light or the sources are in Japanese, which I’ve explained during my review of The Elusive Samurai anime adaptation is nowhere near at a level where I can confidently review the contents. This part is understandable when the studio is busy bringing manga to life in real time, but if nothing is currently being worked on or not set to be for another half-year or so, then there’s really nothing worth keeping secret about the general production part at least, and I say this as a guy who revels in surprises.

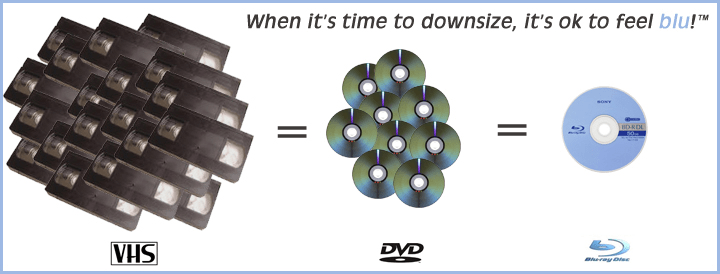

Sometimes information is behind a paywall or a region code and no amount of sloppy-toppy offers will get me access to that succulent content short of a VPN subscription and moving my IP address somewhere else.

Maybe this will help when it comes to viewing the BBC’s documentary on The Troubles

A not insignificant portion of my animanga reviews have my parsing what I can from what I’m able to find in English, the most notable examples on this blog being that of Nazo no Kanojo X and Haibane Renmei, where the mangaka doesn’t have easily accessible photos of themselves or evidence that they’ve done interviews in the past and the other where the eccentric writer pulled an anime adaptation off the cutting room floor of his studio. Who says Haibane Renmei was a final draft at the time?

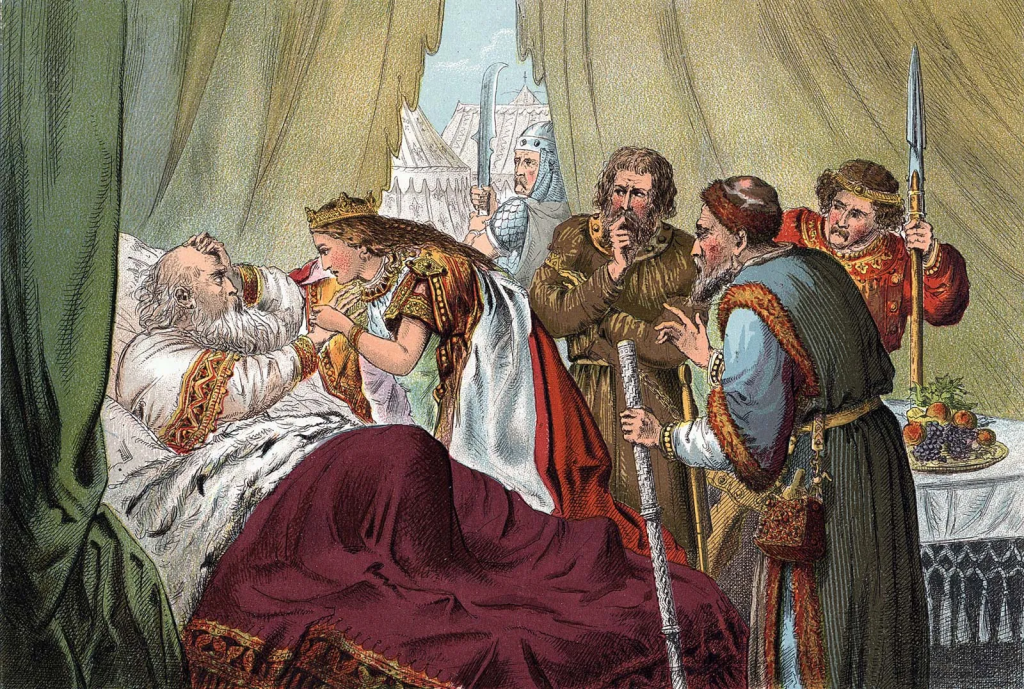

With that said, my recent trip to the cinematic side of things in East Asia is something of a pipeline, I consider. The precise origin point isn’t so much lost as its under tough debate within myself. I would say that it began when I was in community college in 2018 and my Asian Art History professor introduced the class to Akira Kurosawa’s Ran which is a medieval Japanese interpretation Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Japanese romanticization of medieval Europe is a time-honored tradition outside of Isekai, it seems.

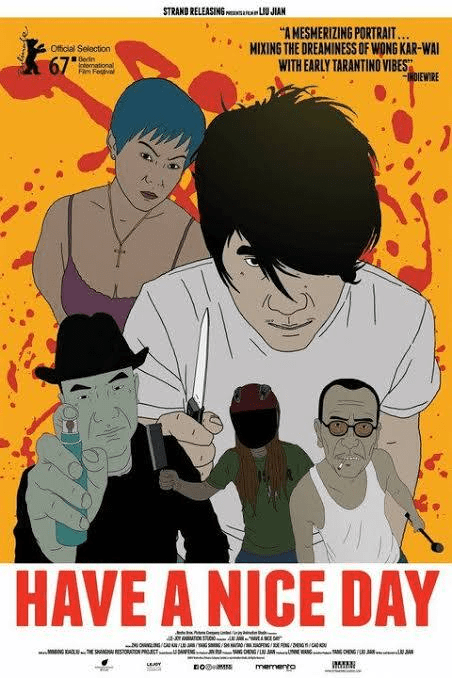

But as I recall, I was on a streaming site whose name I forget where I was made aware of a Chinese-animated and directed film by the name of Have a Nice Day.

Without spoiling too much of the plot, it’s inciting incident is when a cab driver, Xiao Zhang, takes a million yuan ($150,000 USD) at knife point. Not for completely selfish reasons; his girlfriend was the victim of a botched cosmetic surgery and he wants to use the money to get it fixed in South Korea. The rest of the film is something of a No Country For Old Men type of movie, in the sense that even more unscrupulous folks are after the cash, with each pursuer quirkier than the last. Are they dangerous? Yes and no. They are dangerous, but often to themselves than anyone else. And Zhang is still in some kind of danger as some of these types gun for him too, but have to fight the rest of the mob off as they chase him down. One prize, clashing goals, and a story made up of losers and those who lost less. Make of that what you will. It’s currently free to watch on Tubi as of this writing, so I might as well remind myself what I liked about it.

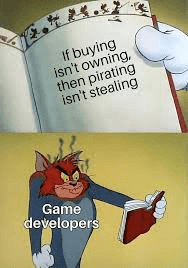

At the time, I was simply looking for movies and content to watch in the dark of night on my ancient Samsung touchscreen laptop. I was 18 turning 19 at the time and the 2AM binge was a fierce mentality. After a few years of that, binging doesn’t do it for me anymore, as I’ve explained in the past. I was scrounging for films I’d heard of but haven’t seen, and without a specific order in mind. Just wait for the lightbulb to flash on, scour the web for a pirate site that’ll allow to me watch or torrent without issue, and I’m on my way. In some cases, I took these with me to the movies during the holidays and because the copyright expired on some of these, I was able to watch them all in the Almighty Internet Archive.

To keep track of all of these, I had a Wordpad document organizing the movies listed by decade, starting with the 1930s black and white films where just about every production member is long dead, the production studio defunct or eaten by another one over the years, and no one left alive to make a fuss over it. Pirating movies is my time-honored tradition, Jake.

Of the films listed, some of these do happen to be Kurosawa films, but looking back at that old document, interspersing Eastern films with the plethora of Western films harkens back to a time when I couldn’t tell the difference between animation and anime, but didn’t care because the drawings moved. You think I gave a damn whether Zatch Bell! or Yu-Gi-Oh! were animated in Vancouver or Yokohama? Seven-year-old me could tell it was art, and it was f[horse]king art!!

Where did this series go, by the way?

Speaking of art, I can talk at length about the production and cost side of even foreign cinema, but aside from country of origin, there really isn’t anything foreign film studios do differently in terms of filming. And yet as far as accessing these films go, it’s historically been a challenge for the simple reason of Hollywood being Hollywood. Harboring the lion’s share of the world’s movies, a foreign film would need an international film festival to get more eyes on it. These days, there’s not much trouble achieving that and more, but in an industry where the mantra is to “know your audience,” dropping a foreign film on an unfamiliar audience can further alienate the audience and hurt the film’s efforts, provided the audience is looking at that sort of thing. It can feel like homework if there isn’t prior exposure to the subject matter.

What does this mean for Asian cinema in the past? Well, long before the interconnected-ness of the modern age, the best you could do was release films of age-old stories, hence why the western film genre dominated from the late 1890s to the 1970s. So powerful and inspirational were these stories of cowboys and Indians that non-American directors took a stab at it by way of the European (mainly Italian) subgenre, the spaghetti western. East Asia, in particular, had to make do with old tropes and stereotypes for specific genres to gain traction over the decades with pioneers like Bruce Lee, John Woo and even Akira Kurosawa gradually introducing these concepts to the western market. The benefit being that their names are known, the drawback being that kung fu, samurai, shinobi, and other medieval concepts were assumed by many to be all that the region had to offer at least until minds like John Woo and Park Chan-wook showed us that even East Asia can cinematic set piece and gun-fu to the top.

Another thing to highlight about Asian cinema would be the local politics. Like it or not, history and politics touches everyone and in the grand scheme of things, East Asia and Southeast Asia have a disturbing tradition of strong men dictators who couldn’t help but meddle in the affairs of private citizens, historically and contemporarily. Mainland China has loosened its grip in recent years, but in some areas the CCP can still put a thumb over film production. Japan is a democracy these days, but pre-war films were heavily scrutinized for dissent from the Meiji era to the mid-Showa era. Post-independence South Korea had a hardline anticommunist stance that kept creatives walking on eggshells in the film industry and (as I’ve discussed before) in their manhwa/comics industry, leaving their manhwa to be discovered decades after publishing online. Needless to say, if the government didn’t like it, it wasn’t gonna get a wide release outside the country, never mind have a guaranteed impact at home. Why bother making uncultured foreigners care about our movies?! We have mouthpieces to produce!!

But we live in a freer world, so that’s not an issue anymore… supposedly… It’s only a recent discovery (or re-discovery if I’m being honest) that I’m adding these films to my watchlist and the showing thus far has been nothing short of:

Insert Invincible title card effect here

I will not stop writing about these films. I’ll use my remaining appendages if my fingers fall off.